This is a re-post

Currency is boring. Let’s make GIFs!

On Friday May 2nd, around 7pm, Kevin McCoy completed transaction #1217706 on the Namecoin block chain. McCoy was taking part in Rhizome’s Seven on Seven, the fifth annual conference pairing up of artists and technologists at the New Museum. And that transaction through Namecoin, one of the countless spinoffs of Bitcoin, created an entry in a public ledger of exactly which bits are changing hands between two people.

But this transaction was different from the millions of other ledger entries tracked by Bitcoin and its variants.

(not monegraph signed)

This time, the bits being traded weren’t just tracking a virtual currency. Instead, they were tied to an original digital artwork created by established artists, becoming the first to follow a new convention called “monegraph”.

Copy and Paste

There has been hand-wringing about the fate of digital artists for at least as long as there has been digital art. But as most everyone’s computers got connected over the last two decades, the most fundamental cause of concern has been the effortlessness with which any given work can be instantly, and perfectly, copied. In a realm where novelty, rarity and exclusivity underpin so much of the (real or perceived) value of a work, copy and paste goes from being an act of creation to an act of destruction.

Reblogging is essential to getting the word out for many digital artists, but potentially devastating to the value of the very work it is promoting. What’s been missing, then, are the instruments that physical artists have used to invent value around their work for centuries — provenance and verification.

Provenance for an artwork can be asserted in countless ways, from witnessing performance art firsthand to having a world-famous auction house bet its credibility on whether a work is an original or not. This function is critical not just in enabling an economic art market, but also in the study and understanding of individual artworks and their context within a movement or culture.

Verification, on the other hand, takes on a new urgency in the digital realm. In this context, verification means the validation that a work is unchanged from its original form, and that the work in question is the actual work being discussed as a creation. It has, of course, always been possible to forge a work (and this is one of the issues meant to be solved in physical art by checking provenance), but there’s a more philosophical debate about verification in the digital realm, where simply viewing an image in a web browser results in a copy being made on the viewer’s computer or phone.

Various efforts have been made to assert forms of provenance and verification for digital art over the past few decades, but most relied on the artworks to remain within closed, proprietary technological silos; few were designed to verify a work while also allowing it to be widely displayed across the Internet. As a result, the only way for artists to really build a market around their digital works has been to convert them into physical forms.

Lemons

At the opposite end of the technological spectrum from experimental artists, we find the Bitcoin community. For the past few years, its members have been boundlessly enthusiastic about a technology that, for most Internet users, is hard to understand and even harder to put to use. We are so used to hyperbole that it may not be clear, but Bitcoin really is a new technology. And the block chain technology that enables it absolutely is groundbreaking.

What the technology behind Bitcoin enables, in short, is the ability to track online trading of a digital object, without relying on any one central authority, by using the block chain as the ledger of transactions. The problem is that the conversation about these inventions is insular even by the standards of the tech industry, populated with fake Satoshis and genuine Winklevii.

Perhaps the most damning critique of the Bitcoin community is to point to what passes for innovation. Bitcoinists tend to focus on a series of nearly-identical clones of the original currency, distinguished only by increasingly esoteric names. There’s Dogecoin, after the ubiquitous shiba pidgin meme. Litecoin, “lite” because it can run on cheaper computers. Coinye came closest to connecting with a working artist, by dint of having been an unauthorized appropriation of Kanye West’s name. What Bitcoin projects mostly haven’t tackled are big challenges in civics or activism or art, aside from is-this-a-joke projects like the Bitcoin Art Gallery. There is no gastrocurrency or cartocurrency. There is only cryptocurrency, an egregious coinage coinage.

It’s increasingly clear that a virtual currency is perhaps the most boring thing one could create with Bitcoin technology.

This disconnect from the real world is pervasive even though some of the biggest names in the venture capital industry have poured tens of millions of dollars into Bitcoin and related technologies. Though it’s still early, the primary focus of this enormous infusion of normocurrency thus far has been a series of “digital wallets”. You know digital wallets — every other year Google, or Microsoft, or Square, or other tech titans try to get you to pay for things by storing your credit card number in their online services. The new products seem to promise to combine the unpopularity of digital wallets with the inscrutability of using Bitcoin in lieu of your credit card.

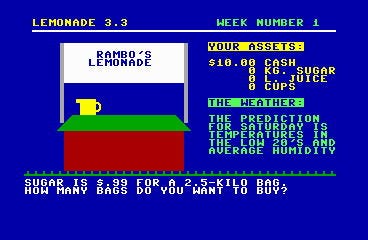

Today’s Bitcoin converts too often sound like someone waxing enthusiastic about the Lemonade Stand game on their old Commodore 64. It’s clear that geeks are having fun creating a virtual market, but it’s hard to understand how almost anyone else would benefit from it.

Chain

Rhizome’s Seven on Seven conference has an august history, bringing together formidable artists with truly credible technologists, at least until I got picked as one of those technologists. Held at the New Museum, this year’s event set the bar high from the start, opening on Saturday morning with a corker of a keynote from Kate Crawford followed by an excerpt from a video of the late Aaron Swartz discussing his 2012 collaboration with Taryn Simon, Image Atlas.

Kate’s characteristically brilliant presentation contextualized normcore and the NSA and drones and Occupy, in case anyone worried that every Big Important Idea couldn’t fit into a single talk. Following that with an evocation of tech’s most besainted young activist was enough to move anyone in the audience, not just those of us who were his friends. And then six pairs of extraordinarily talented artists and technologists followed. We still had a full seven hours to go until we were scheduled to present.

Kevin McCoy and I were batting cleanup together. Kevin and I had met just 48 hours earlier, with no introduction and little instruction except that we would have one day to create something we wanted to share with this audience. Within five minutes of our initial introduction, we knew exactly what we wanted to build. Each of us had been ruminating about the potential applications of Bitcoin’s block chain technology to the realm of digital art for months. Given the pedigree of the event, we knew we would have to at least present an idea worthy of Seven on Seven, even if its execution were necessarily compromised by the 24-hour deadline on which it was created.

I’ll skip past the typical hagiographic creation myth here to instead emphasize the fact that much of this idea was not novel. Indeed, many people have been pondering this exact combination of art and technology — enough that Kevin and I asked each other several times, “Why the hell hasn’t anyone done this before?” Just some of the influences on our thinking:

- In February, Paul Ford outlined non-currency uses of the block chain in MIT Technology Review: “[T]ake digital art. Larry Smith, … an analyst with long experience in digital advertising and digital finance, asks us to ‘imagine digital items that can’t be reproduced.’”

- Rafaël Rozendaal’s sale of If No Yes late last year, relied on the Internet’s conventional Domain Name System (DNS) as the proof of digital uniqueness but galvanized a conversation about digital art sales.

- Manuel Araoz focused on the verification potential of block chains with Proof of Existence, launched two years ago to provide exactly what it says, without trying to address transfer of title to any works it recorded.

- Even otherwise-conventional technology startups have toyed with related ideas, including NeonMob (which uses a closed system to verify provenance) and the as-yet-unlaunched Electric Objects, which seems to focus on the display of digital artworks in the home.

- And Paddy Johnson’s March review of Brad Troemel’s FREEDOM LIGHTS OUR WORLD (FLOW) spoke directly to the potential of block chains in an artistic context:

The kind of subcultural shadiness that’s associated with the crypto-currency seems to indirectly address the concerns of an unregulated art world, and the very structure of the currency provides a direct parallel to how value is constructed in the art world. Like Litecoin’s “block chain,” a built-in algorithm that creates a digital trail of every transaction ever executed, the art market uses provenance to construct value. The coins themselves may be just swag, but they’re now packaged as a known asset class, poised to take on a new value as art.

All of this to say: Ain’t nothin’ new under the sun. And yet, for all the conversation, and all the people who’ve been ruminating on provenance and verification in a digital world, we hadn’t seen the pieces come together until now. That little bit of hacking Kevin did last Friday night may mark the moment that everything went from theory to practice.

Monetized Graphics

Behold:

Monetized Graphics

Jennifer and Kevin McCoy have been digital art pioneers for two decades. Just a brief glimpse at their work zips through television and DVDs and the web and GIFs and sculpture and software. And the themes that emerge push deeply into how we share experiences, what our cultural memory is around media, what becomes of time and distance in a digital world. This is work with meaning, with presence. In more recent pieces, seeing some of these works captured in physical form seems to be constraining them as much as it is containing them. It’s clear the future of their work requires being freed to be even more a part of the Internet.

Exemplifying this evolution is cars.gif. Created by Kevin for the monegraph project from a video that Jennifer and Kevin had created years ago, cars.gif became the first block chain-verified digital original just a few hours after we started working on the project.

We picked the phrase “monetized graphics” on a lark.

Even days later, we never stopped laughing at how “monetized graphics” captured an absurdly crass version of how people would interpret a market for digital art. By the time we would begin to demonstrate the concept, we were sleep-deprived enough that it seemed likely nobody would get the joke. Maybe “monetized graphics” was the kind of thing that only seemed funny if approached with the mindset of an undergrad who’s been cramming for an exam all night.

Fortunately, when we showed the introductory video (above) at the New Museum, the crowd seemed to go along with us. They were in on the joke. We followed the ridiculous video with a quick explanation of the format that Kevin had come up with to ensure provenance and verification, which we had dubbed “monegraph” — a serendipitously pleasing concatenation of “monetized graphics”.

Putting the pieces together

What had become clear was that, for any given digital work, it only takes two steps to ensure its originality. First, a public claim to ownership or creation of that work has to be asserted. And second, that claim and a representation of the work itself has to be captured in the block chain, so there is a public record in the ledger and a way to record any transfers of that title in the future. Thus, there are just three key parts to verifying digital art with monegraph (here with examples of each):

- A work: Your clever animated .gif

- A claim: A public tweet saying that the work is yours

- A record: An entry in the block chain, recording this information in a particular format

Despite being the “technologist” of our pair, I am also a worse programmer than Kevin, so I set about creating a simple website for monegraph that would accept your Twitter login and the web address for your work, and give you a tweet to make your claim, along with the information to put in the block chain record.

Meanwhile, Kevin set about creating the format for that record, ensuring that it would be a flexible and intelligent starting point for these kinds of technologies. While it’s easy to imagine an implementation that might have involved creating yet another new Bitcoin clone, Kevin decided in the interest of expediency to piggyback on Namecoin, which had been designed with a little bit of room for storing extra information like the records we were hoping to create. Namecoin had an existing block chain, and monegraph would make use of it to store its claims. That accommodation in Namecoin’s design was a result of brilliant thinking in the early days of Bitcoin, imagining what its most inventive purposes might be; the definitive articulation of that thinking was in a brief essay by Aaron Swartz.

The worthwhile questions

The end result of a day’s work on monegram is that almost anyone with a Twitter account could claim a digital image, get back a chunk of specially-encoded information representing their record, and then copy and paste that chunk into a Namecoin program and have a verifiable record of their claim. At current Namecoin exchange rates, it costs about four cents to make a record for a new artwork, or to transfer a title to an artwork.

To be sure, this was a hacky way of doing things. The app you have to use to get a Namecoin address and enter in these records looks like some abandoned system utility from Windows 95. There’s presently no place for a normal Internet user to go and even download the Namecoin app because they’re redoing their website. If you have an iPhone, you’ll never have a Namecoin app because Apple doesn’t like Bitcoin and its variants. The state of the art is, well, impossible.

And yet. If you were willing to hunt down the nerdy bits needed, and to put up with the annoyances and inconveniences, something new was happening. In the room at the New Museum, the minute that Kevin transferred ownership of one of his animated GIFs to me (I paid him four bucks out of my wallet in exchange for the Namecoin transaction), it was clear that there’s something interesting here. Some really good questions are being raised:

- Sure, it’s nice if an artist can sell the title to one of their digital works, but what else can we build around the ideas of provenance and verification?

- Assuming that block chains are as secure as they appear to be, what can we do to enable art heists?

- Now that the basic structure of monegraph is laid out, what would an artist-ready experience look like? (Today, the block chain looks like the raw output of a computer program; it’s easy to imagine a block chain of artworks that was displayed more like a Twitter or Tumblr stream.)

- We’ve demonstrated a proof of concept using a GIF image, but what would change if we were trying to use an audio or video clip? What about an app or computer program? What about a whole website?

- How does this intersect with copyright? What changes to intellectual property law might be required? What improvements to IP law might be made?

- How will we get artists ready for the changes that might confront them with these new capabilities? Can we protect the art and its expression?

- Given that monegraph makes no attempt to verify someone’s claims, how will we build trust systems to deal with the inevitable gold rush of people falsely claiming others’ works?

These are the questions that a work like monegraph is meant to enable. But as with any new idea, it can be difficult to reckon with the implications. Steven Melendez asserted that monegraph could “eradicate fake digital art”, when this is exactly backwards. In fact monegraph makes it possible to have “fake digital art”, because prior to this we had no consistent way of defining an “original”.

Fortunately, we’re also seeing people joining the conversation around these ideas. Whitney Mallett summarized some of the most tantalizing potential:

Blockchain-verified digital art could catch on, and if it did, it could create a more traditional model of authorship for net artists as they negotiate the murky world of authorship and ownership online.

What’s clear is that this conversation will be happening in studios and museums, amongst non-profits and artists’ workshops, between coders and curators. Where it doesn’t seem to have taken root is in the most conventional venues of the technology industry. When Kevin and I were asked to represent Seven on Seven by demoing monegraph to the crowd at the TechCrunch Disrupt conference, we began with the title “monetized graphics”, just as we had at the New Museum.

The museum crowd had seen “monetized graphics”, understood the tone and intuitively understood why we’d chosen that ridiculous name. But in a room full of people who were otherwise enthralled by Bitcoin as a technology, the absurdity read instead as a straightforward goal, eliciting almost no reaction. We explained the details of Namecoin transaction #1217706, and why it was significant to artists and creators of all stripes.

There were no questions from the audience.

Thanks to Quinn Norton, Kevin McCoy, Rex Sorgatz, Kate Lee, Evan Hansen, Zeynep Tufekci, Clive Thompson, and Paul Ford

I have read your article carefully and I agree with you very much. This has provided a great help for my thesis writing, and I will seriously improve it. However, I don’t know much about a certain place. Can you help me?